On June 9, 2013 I gave a talk at Seattle Children’s Hospital during an annual memorial service for parents who’ve lost a child. Because it was deeply personal, I didn’t plan to share this with anyone else. But in the nearly two years since, I’ve changed my mind.

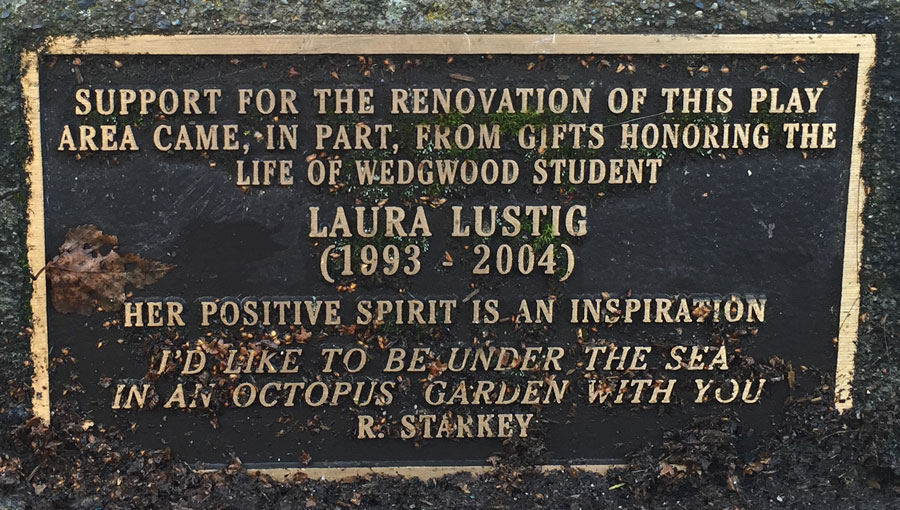

Eventually, we all suffer losses. On the chance, this might help you deal with yours, I’m making this available. Also, it’s a way of honoring my daughter Laura (who would’ve turned 22 today) as well as some of the other dear people I’ve lost over the years. Happy Birthday, Laura.

As parents one of the first things we have to learn is patience. Patience because kids do things at their own speed. Patience because kids rarely do things when we want them to—which is immediately.

And patience because kids always expect us to do things for them when they want us to—which is immediately!

Patience—a different sort of patience—is even more important now.

I’ve been blessed to have had three children. Blessed even though two of them have died.

They died at very different points in my life and under very different circumstances.

In 1982, Karen Lavik Lustig—my high school sweetheart—and I had been very happily married for 9 years and we were expecting our first child. Karen wanted to do this as naturally as possible—out of hospital with a midwife. So that’s what we did.

But during labor, Karen’s blood pressure exploded and she had a seizure.

Unconscious—and as it turns out far worse than unconscious—Karen was rushed to University Hospital where doctors did what they needed to do to deliver our son Logan.

He only lived a few minutes.

About an hour later, a nurse brought Logan to me and I held my dead son. That was the first time I’d ever cried as an adult.

Although I was devastated, my attention quickly shifted to my wife. But Karen never regained consciousness. She’d had a cerebral hemorrhage and a little over 24 hours later she officially died.

I grew up in Seattle. I had family and friends here, but I was young, in shock and I really felt alone in a way that is hard to describe.

Frankly, I did think about suicide. Who wouldn’t? But I’m an inordinately stubborn person. So I decided to hold on for awhile. Tough it out. See what happens.

And then, about seven very strange months later, I was back in a hospital again. My mom was having a mastectomy. And, the last night she was there, I met this incredibly warm, funny nurse named Shelagh.

Now I wasn’t looking for a date. (And <pause> I don’t recommend going to hospitals to pick up nurses. I understand hospitals frown on that sort of thing—at least these days.)

Never-the-less, a week later Shelagh and I were dating. And the following year we were married.

Another thing I don’t recommend? Grief as an aphrodisiac. It’s hard on any relationship. Most people who get remarried within a year, end up getting divorced—often within the next year.

So it wasn’t easy. But Shelagh had an amazing amount of patience with me. And a few years later it was my turn to be patient—or at least hold on to hope—because Shelagh wanted to have a baby with me. She wanted a family.

As you can imagine—because of Karen and Logan—this was not an easy thing for me. But eventually I decided…we’d go for it!

And, after some fun, lo and behold…we had our first child—Caitie. And, it turned out, I loved being a father. So, great.

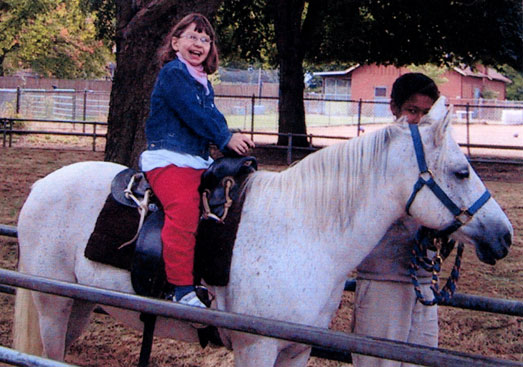

A few years later when Shelagh wanted to have another child, I resisted considerably less. And we had another beautiful daughter—Laura.

Healthwise, there were some early warning signs, but it would be about four months before we knew for certain that anything was seriously wrong. When breastfeeding, Laura would choke and turn blue—repeatedly.

It turned out she had extremely low muscle tone. Later, we also discovered that she was having small seizures, was developmentally delayed and had an immune system that was basically wide open.

Eventually, with medication Laura’s seizures stopped and then disappeared completely. With time—despite her low muscle tone–she gained better control of her body and was able to walk (at three) and say a few words when she grew older. Every three weeks, infusions of Immune Globulin here at Children’s brought her immune system up high enough so that she could attend public school—which she absolutely loved.

We had to take her out of school any time other students had chicken pox or anything more serious than a cold. But—as the years passed and she stayed pretty healthy—most of the time—I stopped worrying that her life might be short.

And the weirdest thing happened. I realized that we were happy. Not in spite of Laura, but because of Laura.

She was the happiest, friendliest person I’ve ever known. Most people have to be on drugs to be that happy. But Laura was naturally happy.

Not every moment. She could have temper tantrums like any other kid. (Eat vegetables. Noooo!)

And Laura could be bossy—especially if she thought you weren’t doing the right thing—weren’t following the rules.

She took people very literally. If you said, “I should go” And you got up to go. Then you didn’t go—she’d start pushing you (gently) out the door.

And Laura had her own rules. If I was in my office and sneezed, she’d get a Kleenex and bring it upstairs to me—whether I needed it or not. Because she wanted to be helpful.

She’d often be helpful at school too—whether the teachers wanted it or not. If any of Laura’s classmates got confused and sat in the wrong seat or went the wrong way—Laura became the traffic cop who let them know where they were supposed to go.

And yet, Little Miss Bossy was also one of the most popular kids at her school. Despite her inability—because of low muscle tone—to be able to say much either verbally or through sign language—she was an incredible communicator.

And the thing that she communicated the most often was her joy whenever she saw friends or family.

At the very least, you’d get a big smile and a Laura wave [At this point, I break into a big smile and wave energetically at everyone.) But family and good friends—many of whom as she matured were increasingly boys—would also get a loving Laura hug.

Because Laura wasn’t very verbal, it was easy to underestimate her and I suspect some people might have mistaken her happiness as some sort of mindless bliss.

But there was a real and complex person inside her. She wasn’t unaware of sadness or pain. If anything, she was an emotional genius. She wanted you to feel better. And you did.

Laura did a better job of making people feel better then anyone I’ve ever known. And because of her I learned that all children—every person—is valuable and can contribute something crucially important to life.

<pause>

But then, one morning when she was 10, I went to get Laura up and I discovered that she was paralyzed on one side of her body.

Instead of a stroke, we eventually found out that a virus—a completely benign virus for most of us—had overwhelmed her fragile immune system. Laura spent a week at Children’s in a medically induced coma as doctors tried to calm her system down.

Towards the end of that week, doctors told us there wasn’t any hope. A couple of days later, we had Laura disconnected from life support and she died peacefully in our arms.

My first reaction when we learned that Laura was going to die was—oh, God. Not again. I can’t go through this.

Except, deep, deep down I knew I could.

I knew the kind of overwhelming pain that was coming. I’d been through it before—different, but close enough. And I knew—even though I wouldn’t feel like it—I could make it.

I also knew that this time Shelagh and Caitie would be there and we’d be sharing the pain.

What I didn’t realize immediately—but that you’ve all no doubt found out—is that people experience grief in different ways and at different speeds. And there are flare-ups when you least expect them.

Time doesn’t heal all wounds. It can help. It can help a lot. But losing a child isn’t a wound. It’s literally losing a part of yourself.

So I don’t want to make this sound easy. It’s not. Any particular moment can be overwhelming.

I’m still working on some of this.

But I know you can survive. And that it can get better—impossible as it may seem.

But you need patience. Patience for the ones you love. And patience for yourself.

Beautifully written–I would expect that from John. This lovely outpouring will make others loss easier to understand. Thank you, John. I’m proud to know you as a friend.

I remember when Shelagh was pregnant with Caitie and you were a bundle of nerves. I was too, but I didn’t admit it. I tried to be a support to you, and several times I said, “Lightning doesn’t strike twice!” But sometimes it does.

Such events take a toll on all of us. I figuratively held my breath throughout that entire pregnancy, and every one I’ve known of since. And my heart broke all over again when I heard the news of Laura’s loss. Although I was fortunate enough not to experience it first-hand, I have always felt that there can be no greater loss than for a parent to lose a child. And to lose two is unimaginable.

Thank you for sharing your story.

Thanks for sharing your story, good reminder that others have grief yet survive, though the pain continues. Also, she seemed like she had a great heart for helping others, while we adults may not care so much for others. And thank you for reminding us we need to be more patient and value those around us, not wait for a funeral to express our appreciation.

You did well in expressing the story with your usual warmth and humor, while honestly taking us through the hard times with you. Thank you for publishing this.

Thanks for sharing. I met Shelag in Vancouver in July at a family reunion and hope to some day travel to Seattle. We all carry hurts and wounds known only to ourselves. Sometimes when the wound is fresh, we want the world to cry with us, but no one knows the depths of our pain.

Thank you, Cousin Louise. I hope you make it to Seattle one of these days and I get to meet you. Shelagh says, “Hi!”

Love you John, for being man enough to share this. I honor Laura, Shelagh and you.

Thank you very much, Jeanette!

Such a powerful and emotional story, John. I truly have no words. I knew you had lost your daughter but that’s all I knew.

You’re a good man and a wonderful father and husband.

God bless all of you!

Thank you, Jeff.

John, your genius is in your genuineness. Thank you for sharing this. I’m not sure what to say that would fit here, other than that I love, respect and am inspired by you. Much love from my entire family, to your entire family.

Thanks, Luke. Much love to you, Laurie and your family!